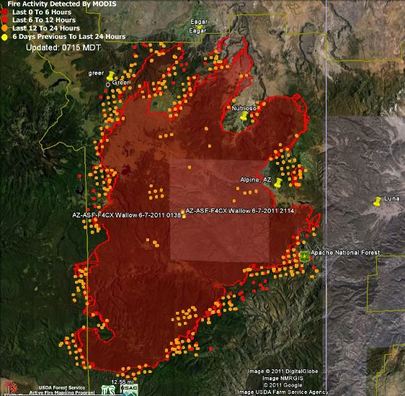

The Wallow Fire started fast and got big faster. On the third day, it went from about 6,700 acres to 40,000 and over the next seven days, it consumed the following acreage:

Upon arriving, I was assigned to lead the Media Group and it was not soon after that it became evident we were not functioning well. Information was too detailed, too fluid, too much, and too frequent for consistency between individual PIOs (and some of those PIOs were, by necessity, forced into roles beyond their capacity). After hearing complaints from both PIOs and media, we held an impromptu press briefing. We then committed to twice-daily briefings and things seemed to settle down a bit for the media, but not for us. What follows are some thoughts on media briefings and large incident issues in general. Much of this post is based off of a piece I wrote soon after leaving the incident, so some of you may have seen that earlier version.  First Wallow Fire briefing. First Wallow Fire briefing. Organization It will be tempting to place the person providing the media briefings in charge of the group of media PIOs. In most cases this will work, but on an incident like Wallow or Rodeo-Chedeski or Hayman, it would be better to separate the Briefer from the Media Lead. On Wallow, I was in charge of 12-14 PIOs (or more?) and I was never able to interact with them like I would have preferred. There was so much work involved in prepping for the briefings and tracking down rumors and information that I did not provide good service to the Media PIOs and certainly did not have time to mentor trainees. When we are dealing with these kinds of incidents, I think it would be wise to have the briefer stand alone in the PIO organization and have a separate media lead to manage the assignments and take care of the other PIOs working with media. Additionally, having a strong PIO2 or PIO1(T) attached to the briefer to help run information down and provide support would be ideal. (Mega incidents seem like they would be good training assignments because there is so much going on, but in reality, they are tough for trainees. You are likely to get assigned a task and be stuck with it day after day simply because the Lead PIOs don't have the bandwidth to manage the organization in a way that provides you with a variety of assignments. If you find yourself in this position, do the job you're assigned, but also look to train yourself: watch the team dynamics, watch how other PIOs interact, take the measure of the stress throughout the incident. Even if you are answering phones all day or spending a week in an evacuation center, there are many non-taskbook things to learn.) It is critical that the briefer have a strong relationship with the team. On Wallow, I was fortunate to be attached to the same team that I had worked with for several of my PIO1 training assignments. I knew Ops, Plans, and the IC Trainee quite well. We also had an excellent PIO acting as PIO Liaison to Operations. (I think his name was Brad.) Those relationships were invaluable and I cannot imagine making it through the briefings without the information I gleaned from informal interactions based on those trusting relationships already in place. What that means for most IMTs, I think, is that a Team PIO will have to do the briefings. So, if a Team PIO is needed to do the briefings it will be difficult for the IMT because that PIO will no longer be able to attend to all the team demands and help run the PIO organization. If you are in a pinch and the briefings fall on you, order some trusted folks immediately to take on as much of the management load as possible and if you have to, make the case with the IC and the GACC to get name requests through. When Wallow occurred, there were not that many PIOs who had experience with major media briefings and for a couple of years after the fire, I would get requests to be the spokesperson for some large fires. I turned those down because I was not familiar with the IMT and felt we needed to grow more PIOs who were capable. We should encourage this and continue to add to our capacity through mentoring and training. We need to get to the point where every Type I IMT and most of the Type 2 IMTs can handle a major briefing. A trend I don't like is to turn over briefings to the IC or Operations. On a Type 1+ incident, those folks are going to be busy enough and will not have time to research possible questions, making it too easy for them to provide an unsatisfactory answer to a non-operational inquiry. If they just provide a briefing and the PIO answers the questions, can't we assume the PIO has a decent understanding of the operational issues? If so, why not take the burden off others and just have the PIO provide the briefing? It's our job and we need to own it. Now, yet another mention of the PIO qualification problem: It is no secret that there can be a great disparity in skills between like-typed PIOs. On Wallow, name requests were shut down and as a consequence, the mid-level PIO leadership was not as strong as it needed to be. Additionally, many of the best PIOs who could be trusted to work independently and make good decisions were necessarily assigned to the Media Group. This greatly affected the capacity of the rest of the organization. Lead PIOs have to be able to match the demands of the incident with the known skills of available PIOs. When you have 100 or so PIOs, a trapline encompassing 4,000 square miles, satellite info centers in towns and evacuation centers, a crushing social media load, and unfortunate events like blackouts and Inciweb crashes, you have to have people that can be trusted to make good decisions throughout the organization. You also have to build an organization that can faithfully relay info up and down the PIO chain. As the span of control approaches the highly complex, making do with whoever ROSS provides becomes a bit of a gamble. I would suggest we ask the ICs to approach NICC and advocate for a limited number of PIO name requests per mega incident. After that, we can agree with the GACC to fill in the organization with blanket ROSS requests and accept all that are willing to come. Information On fires like Wallow, you do not have time to sufficiently monitor the media. The incident is too demanding and the media coverage is too wide. It seems you can maintain a decent awareness of local and regional media because you can at least intermittently interact with those reporters, but the national and international coverage is much more difficult to follow. Related to that is the awareness of how the information you are providing to the media is being received up the management line. Your awareness regarding this is limited to the local agency or the GACC at best. When you add intense political interest to the bubble we operate in, you start to get a little paranoid regarding the higher-ups. To that end, I would highly recommend that whoever is sitting in the NIFC PAO chair at the time start a daily five minute or so call with the Briefer to discuss any problems with national coverage or any concerns from the NIFC/WO perspective. During Wallow, I finally managed to talk to NIFC a few days in and their support and advice helped me do much better in the briefings. The conversation also greatly eased my concern that there were issues I was not adequately addressing. When there are multiple IMTs on the incident but your zone seems to be the media hub, it is important to establish good relationships with the other teams and provide solid information about what they are accomplishing. For most of the time I was briefing media, I felt like I was failing in this regard as I was not getting good information on the South Zone of the fire and could only speak generally about what was happening on that end. In retrospect, I should have worked harder at establishing and maintaining those contacts. Social media was big back then but compared to today, it was peanuts. Wallow was the first fire where I would check in with the Social Media Group to see what rumors they were picking up, what the community was saying, where the inconsistency in our messages was showing up, and everything else that was possible to glean. The interaction helped inform the briefings and allowed me to anticipate questions I would have been blindsided by otherwise.  Talking to the map instead of the media. Talking to the map instead of the media. The Briefing After Rodeo-Chedeski and the first couple of Wallow briefings, I started pulling together lessons on how to organize the media briefings more effectively. Thinking through the process is just as important as the answers you give. Be prepared. Be able to discuss the entire incident. Think through themes you might want to emphasize. Work through the rest of the PIO organization, including social media, to anticipate questions ar identify areas that need clarification or context. Don't rely on notes for your narrative. (I tried to memorize all the basic numbers for each briefing, but did carry a small note with acreage, containment, personnel, and aircraft written down. Sometimes I had to check it, others not.) Be calm. Don't rush your words. Pay attention to your distance from the mics. Choose the best possible backdrop. You don't want to be talking in front of a dumpster or a non-descript building if you can help it. Sometimes you can't, but try to set it up so there is at least something incident-related in the background. On incidents that are geographic in nature, make sure you have a current and large map. Maps are important in explaining what is happening and if you freeze up for a second, a quick look at the map can jog your memory and allow you to move forward. But remember your audience and don't talk to the map, but with it. Also, with so many stations becoming pre-programmed corporate outlets, we tend to forget about radio. However, there are still true local stations out there and most population centers have at least one news station that covers local happenings. When giving a briefing, it is easy to fall into the visual trap and rely on the map to help you explain things. That doesn't work with live radio. You have to remind yourself to be more descriptive and talk like people cannot see the map. Check in with the media beforehand and establish the ground-rules. Ideally, you have some time to visit each outlet and have an informal conversation and start to establish relationships. Since you don't always have time to do that, I make it a point of going out at least 15 minutes prior to the briefing. I'll first introduce myself and provide the name spelling so we don't get bogged down with that at the start of the briefing. After that formality, I start with questions that show I recognize the media world and am trying to be responsive to their needs. I then move on to how I want the briefing to go:

The reason you commit to answering questions for an indeterminate length of time is that a briefing rarely if ever goes beyond 25 minutes, with most I've done coming in between 20 and 23 minutes. That time seems appropriate and you might as well get credit in good will for what will like happen naturally. If you put a time limit on it, you greatly increase the chance of the media becoming more adversarial. Still, I can see why some would put a time limit and I know the Coast Guard has a general rule of 15 minutes. So, personal and agency preference has to be considered. My thinking is that it's a crisis and we should be open and available so I don't go with a time limit. Speaking of time, you will inevitably overestimate the time spent briefing and I suspect stress has something to do with it. The first few times I was shocked by the actual length after the clock in my head kept telling me 30-35 minutes. Since then I've kept track and routinely think the briefing went 7-10 minutes longer than it really did. I mention this, because around the 15-18 minute mark, I will start to feel a little unease about the amount of time. If it happens to you, recognize it so you can dismiss it and stay mentally dialed in for the rest of the briefing. In short, don't be like this guy: www.youtube.com/watch?v=fMswD3zocts. Stay in Your Lane

For the last several (many) years, we have been told to “talk to the fire” and refer anything else up the line. I can see the rationale behind that position, and it generally holds up on most incidents. However, if I’m doing a briefing that is being broadcast live across the country (and to evacuees, politicians, and all others affected by the fire) and I get a policy question to which I know the answer, I’m probably going to answer the question or at least use it as a bridge to get around to a point I really want to make. To answer a question on things like policy, aircraft, etc., by merely providing a referral to NIFC PAOs will immediately dent your credibility and not serve the people affected by the incident. If we’re willing to take the responsibility and stress of doing briefings at that level, NIFC and the WO should trust us to not screw up too badly. We should have the same freedom to do the right thing in information that we do in operational strategy and tactics. Again, I’m not talking about your average PIO on the trapline or in front of the Post Office, but a PIO1 on a major incident with the media broadcasting every word. When briefing the media on the Wallow Fire, I struggled mightily with this problem the first few days. I was constantly trying to compartmentalize the information that would fall under policy and not directly relate to the incident. Consequently, I stumbled a few times on some basic questions as I ran into that mental dividing wall between policy/incident. After a few fumbles, I ignored the dividing line unless I really did not know the answer. It was clear to me on Wallow (and subsequent assignments) that if we had the approved freedom to speak to issues, the stress would be less. In other words, I think that by drawing such a line in what we can talk about we ultimately put more stress on the PIO and increase the chance of a mistake or misunderstanding. Conversely, if we could talk about everything, well, that’s more liberating, less stressful, and generates a more favorable, professional opinion from those watching. Expecting us to walk the line on a large complicated incident (with VLATs) is unrealistic. Of course, this also places a greater burden on the PIO to be familiar with the larger issues. The wildland firefighting community has a tremendously favorable public image created by doing a great job with skill and competence. When we start to deflect or refer questions to more “authoritative” sources, it damages our image of competence and it will not take much for us to lose the public trust and be thought of as just another government program. I also think we are a robust enough organization that we can handle and explain small discrepancies. If all else fails, there’s always the “mapping error” line. ____ Jim Copyright © Jim Whittington, 2018, All rights reserved. Academic use approved with notification and attribution.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Occasional thoughts on incident response, crisis communications, wildland fire, and other topics.

Docendo disco, scribendo cogito. Blog DOB: 4/26/2018Copyright © Jim Whittington, 2019. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed