Before I found my way to land management agencies and the world of wildfire and incident response, I wanted to be a history professor. My undergraduate degree is in history and I went off to grad school for an MA in US History, writing a scintillating thesis on the Federal Farm Loan Act of 1916--still a big hit at cocktail parties. By the time I started PIO work, I had a decent general knowledge of western US history but soon found myself reading more on the topic because I wanted to understand the communities I would be serving. I always feel more confident and empathetic when I head into an incident carrying knowledge of the history of the place. I think it also helps build credibility if you show the locals you know about their history or if you're able to frame statements in a way that reflects and aligns with the local history. (Maybe it's just me and my inclination towards history though.)

1 Comment

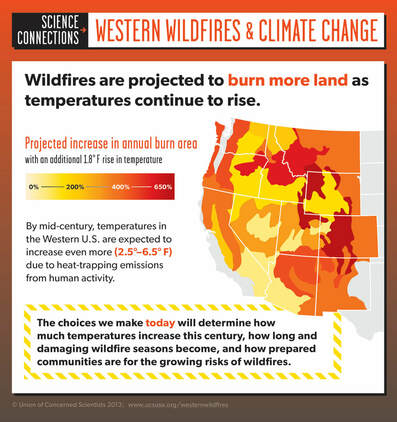

In the wildfire world and presumably, the rest of the emergency management world, we have standardized task books but little instruction on how to fill them out and much less on how to evaluate trainees. Most of us rely on our own trainee experiences to inform how we should mark up a task book and interact with our trainees. My own time as a trainee was frustrating because senior PIOs used different criteria to sign off on tasks, not to mention being all over the board on how to put initials in the book. Once I became one of those senior PIOs, the lack of standards and protocols created several (and sometimes difficult) conversations where the trainee was adamant about what tasks I should sign off on. I've also been known to question the parentage of a previous PIO who signed a trainee's task book in a manner contrary to my approach. So, given that there are few standards, here's how I look at PIO task books and training assignments. I hope this helps others work their way through the process. A reminder: Having a signed task book does not make you a good PIO any more than a law degree makes a good lawyer. Both jobs demand extensive experience, tutelage, and continuous learning.  I don’t see how we can’t talk about climate change. The facts are overwhelming, the science is sound, and our wildland fire experiences validate both. Now, I get that the topic is uncomfortable and I certainly get that while not official policy, not saying much if anything about climate change is a preference that has been well communicated by the current administration. Obviously, it’s a political minefield and I’m not advocating climbing on top of the soapbox and preaching. Most of the time, I don’t think communicators on wildland fires or other disasters should bring it up. But neither should we shy away from discussing climate change when it is appropriate or when asked by the public, stakeholders, cooperators, or the media. As incident responders, we have the obligation to honestly confront reality and as true crisis communicators we have a responsibility to discuss that reality in a way that establishes competence and confidence. If we dance around the topic in an obvious fashion, we damage our standing and the public’s view of our expertise.

I sat down with Brad Pitassi, who is a PIO1 Lead on one of the Southwest National IMTs when he is not a Captain and PIO for the City of Maricopa Fire Department. We discussed Brad's career, the differences between PIOs and PAOs, the need to understand policy and strategy on dynamic and complex events, continuous learning, the training process, and what traits we like to see in a good PIO.

|

Occasional thoughts on incident response, crisis communications, wildland fire, and other topics.

Docendo disco, scribendo cogito. Blog DOB: 4/26/2018Copyright © Jim Whittington, 2019. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed