|

As our incidents trend towards greater complexity, there is a call for incident management teams to be more strategic in their approach across all functions. When strategy comes up, we in the wildfire world have a saying that has been repeated thousands of times: "Fly at 30,000 feet." This always seemed a little off to me because the expected action is that you look down from 30,000 feet so you can see the entire incident and thus you're able to make better decisions. Many times in my career while working towards the Lead PIO position on an IMT, I was told to fly that high but I was never told what I should be looking for from that height. I finally realized that 30,000 feet is a refuge we (including me more than a few times) seek when we know what needs to be done but can't describe it very well. The conversation always plays out this way: the experienced hand is working with a novice, hits a communications roadblock, and the only out is to implore the less experienced person to fly high. Meanwhile, the recipient of this wisdom is looking a little perplexed and nods with an understanding that is not wholly there. After going through our training process and being beat up on many incidents, I finally figured out that the key to flying at 30,000 feet is to not only look down, but to also look out in both time and space. Where are we headed and when will we get there? Where time and space intersect, strategic thinking is demanded. In strategy it is important to see distant things as if they were close and to take a distanced view of close things.

4 Comments

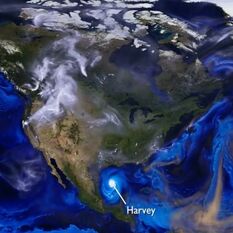

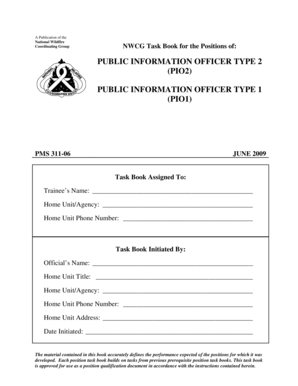

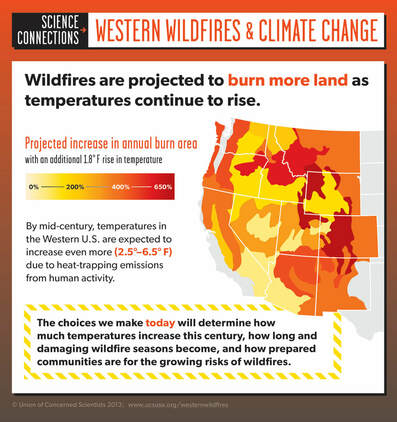

You don't have to be a journalism professor to see that national media coverage of hurricanes and wildfires are different in both style and duration. You see it most dramatically when there are a small number of active fires with large impacts happening at about the same time as a hurricane hitting the US coastline. It's even more acute when an incident like the Camp Fire is responsible for more lives lost and perhaps just as much property damage as a typical hurricane. Or the Woolsey Fire where there are deaths and 200,000 residents evacuated. People wonder why the national media is not sending their top anchors to report continuously from the fire lines like they do from the beaches during a hurricane.  Before I found my way to land management agencies and the world of wildfire and incident response, I wanted to be a history professor. My undergraduate degree is in history and I went off to grad school for an MA in US History, writing a scintillating thesis on the Federal Farm Loan Act of 1916--still a big hit at cocktail parties. By the time I started PIO work, I had a decent general knowledge of western US history but soon found myself reading more on the topic because I wanted to understand the communities I would be serving. I always feel more confident and empathetic when I head into an incident carrying knowledge of the history of the place. I think it also helps build credibility if you show the locals you know about their history or if you're able to frame statements in a way that reflects and aligns with the local history. (Maybe it's just me and my inclination towards history though.)  In the wildfire world and presumably, the rest of the emergency management world, we have standardized task books but little instruction on how to fill them out and much less on how to evaluate trainees. Most of us rely on our own trainee experiences to inform how we should mark up a task book and interact with our trainees. My own time as a trainee was frustrating because senior PIOs used different criteria to sign off on tasks, not to mention being all over the board on how to put initials in the book. Once I became one of those senior PIOs, the lack of standards and protocols created several (and sometimes difficult) conversations where the trainee was adamant about what tasks I should sign off on. I've also been known to question the parentage of a previous PIO who signed a trainee's task book in a manner contrary to my approach. So, given that there are few standards, here's how I look at PIO task books and training assignments. I hope this helps others work their way through the process. A reminder: Having a signed task book does not make you a good PIO any more than a law degree makes a good lawyer. Both jobs demand extensive experience, tutelage, and continuous learning.  I don’t see how we can’t talk about climate change. The facts are overwhelming, the science is sound, and our wildland fire experiences validate both. Now, I get that the topic is uncomfortable and I certainly get that while not official policy, not saying much if anything about climate change is a preference that has been well communicated by the current administration. Obviously, it’s a political minefield and I’m not advocating climbing on top of the soapbox and preaching. Most of the time, I don’t think communicators on wildland fires or other disasters should bring it up. But neither should we shy away from discussing climate change when it is appropriate or when asked by the public, stakeholders, cooperators, or the media. As incident responders, we have the obligation to honestly confront reality and as true crisis communicators we have a responsibility to discuss that reality in a way that establishes competence and confidence. If we dance around the topic in an obvious fashion, we damage our standing and the public’s view of our expertise.

I sat down with Brad Pitassi, who is a PIO1 Lead on one of the Southwest National IMTs when he is not a Captain and PIO for the City of Maricopa Fire Department. We discussed Brad's career, the differences between PIOs and PAOs, the need to understand policy and strategy on dynamic and complex events, continuous learning, the training process, and what traits we like to see in a good PIO.

The AP Stylebook Twitter feed (a good follow) posted this today: Use square miles to describe the size of fires. The fire has burned nearly 4 1/2 square miles of hilly brush land. Use acres only when the fire is less than a square mile. When possible, be descriptive: The fire is the size of Denver. They don't give a rationale, but one can guess it's because the size of an acre escapes more and more readers. However, we talk in acres because it is our wildland fire cultural and bureaucratic default. PIOs should recognize this issue and assist media and the public in understanding the size of incidents by covering both bases: "The fire is X acres, which is about the size of Y."

|

Occasional thoughts on incident response, crisis communications, wildland fire, and other topics.

Docendo disco, scribendo cogito. Blog DOB: 4/26/2018Copyright © Jim Whittington, 2019. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed