|

Soon after the Yarnell Hill Fire, I wrote a paper on my thoughts and experiences. Considering the passage of time and additional assignments, I might change a few things on the periphery but I think the paper stands up well. I did not want to re-write it and I struggled on how to approach this topic for more than a few days. I decided to do a play-by-play of a briefing I gave on the Yarnell Hill Fire. I post this not to call attention to my being there, but because it was a tough briefing and unlike with other briefings out there, I can tell you what I was thinking and feeling as I analyze the questions and answers. (As I noted in Part 1, I would not have been able to do this without the experiences on Wallow and Rodeo-Chedeski.)

I believe this was the Wednesday after the Sunday fatalities and it is the day the Granite Mountain crew buggies were to be returned to their home in Prescott. The media is congregated at a roadblock on the side of the highway leading into Peoples Valley and Yarnell. The plan was for the crew buggies to leave the fire area and pass by us around 10:00, after which I would brief the media. However, there were delays and when the video starts, it is after 11:00 with no sign of the rigs. By that time, it was hitting 100 degrees and you could tell the media personnel were getting short-tempered after standing by for well over an hour. As a result, they started asking questions without a formal start to the briefing. Also, I never wear a radio for briefings, but had one on here so I could monitor the traffic about the crew buggie transport and planned to take it off as soon as I knew they were headed towards us. So, for perhaps the most difficult briefing in my career, everything was going wrong at the start.

1 Comment

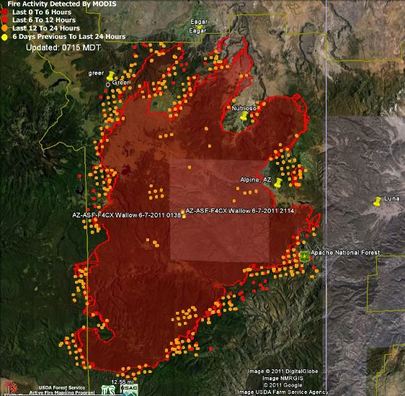

The Wallow Fire started fast and got big faster. On the third day, it went from about 6,700 acres to 40,000 and over the next seven days, it consumed the following acreage:

Upon arriving, I was assigned to lead the Media Group and it was not soon after that it became evident we were not functioning well. Information was too detailed, too fluid, too much, and too frequent for consistency between individual PIOs (and some of those PIOs were, by necessity, forced into roles beyond their capacity). After hearing complaints from both PIOs and media, we held an impromptu press briefing. We then committed to twice-daily briefings and things seemed to settle down a bit for the media, but not for us. What follows are some thoughts on media briefings and large incident issues in general. Much of this post is based off of a piece I wrote soon after leaving the incident, so some of you may have seen that earlier version. Many organizations require their employees to undergo regular training on personal ethics. The goal of these trainings is to expose one to the common humanity and encourage you to not be a jerk. Yet while we spend numerous hours on the personal, we rarely talk about the larger ethical issues revolving around what we do as organizations--in this case, as emergency responders--even though many of the decisions we make before and during a crisis have ethical dimensions. For example, in the wildland fire world, we routinely prioritize the protection of communities and major infrastructure over individual homes, smaller clumps of structures, and other values when suppression resources are tight and the number of incidents are large. Is this right? Is it moral? Ethical? Is it ethical for leadership to place those decisions on IMTs and other responders? Is it ethical for the decisions to be made without an extensive public discussion about the values that will be applied to those decisions? To the nonspecialist, disasters have an accidental nature which is related to the factor of surprise when they occur: the normal, structured, everyday aspect of some form of human life is suddenly and directly ruptured via events that initially exceed customary social and physical prediction and control. This... together with a historical and contemporary certainty that some disasters will occur in the near and intermediate future, renders the inevitable fact of disaster a compelling moral or ethical subject. Human well-being and harm will be at stake in ensuing disasters, and this in itself creates moral obligations to prepare for disaster and reflect on the moral principles that do or do not apply in responding to disaster. Of all the things to read about this day, the FDNY oral histories stand alone. I'm partial to the one by Firefighter Robert Siragusa because he captures the idea of service we all strive towards: Everybody was kind of pretty much in shock at that time. We didn't know what the hell was going on or what to do. So we regrouped with a bunch of firemen. With a bunch of guys we regrouped. We just came back to the front of the building again. This time it was a bigger mess than it was the first time. A lot of the guys just went right to work after that. They just got right back in that rubble, started looking for people. "So we regrouped." And they went to work.

The whole thing is worth a read, as are many others. ___ Jim In times of change, learners inherit the Earth, while the learned find themselves beautifully equipped to deal with a world that no longer exists. --Eric Hoffer Preston Cline is a Wharton guy who recently finished his PhD on mission critical teams. He's smart, generous, and a dynamic speaker. I was honored to read a draft of his dissertation and just received a copy of his finished product. It's full of good stuff that's applicable to incident management and in the future, I'm sure I will reference his work regularly and pay particular attention to the points about developing, conveying, and sustaining expertise. On that topic, perhaps the most thought-provoking passage comes in Preston's introduction: In the fall of 2013, I asked Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel Prize winner in economics, the following question: “What happens to experts when the rate of change exceeds the rate of learning?” His immediate answer was “they cease being experts” (Kahneman, 2013). Indeed. We see the passing-by of former experts regularly. People step out of the stream and can never quite make it back to where they were. But what happens to a profession or an organization when the rate of change exceeds the rate of learning for all of the experts in that field or group? What happens when the problems are too dynamic to work out completely or for the answers to have consistency across time? It seems there are many organizations struggling with this potentiality. In the wildland fire world, we have recently seen a change in how S-520-Advanced Incident Management is taught. Where once it was a "do as I did" experience, today it is evolving into a strategic thinking and stress management class based on adult learning concepts. (Preston's thoughts contributed greatly to this change.) These ideas are slowly working their way through the system. For instance, we also have a movement underway to refine how incident objectives are written so that all responders understand the why behind the what. In the face of rapid change and quickly evolving complexities, we will certainly have to rethink our definition of expertise. Expertise must move from the how and what to the why, from specific knowledge to a higher level of strategic thinking born of experience. Art based on craft. Yet in our world, it also means exposure to a conflict: the drive for certainty (science) and uniformity (legalities) that we see in so many other parts of our society against the uncertainty of incidents, crises, and emergencies that we regularly encounter. Scripted plays versus improvisation out of necessity. (It is most acute after fatalities or serious accidents.) This conflict places a burden on all of us, including academics studying our field, to better explain why we do what we do and to place in context the uncertainties that compel our decisions. There's also a need for doing more at the C&G level. The strategic thinking must now always be there on any extended incident of any type. However, for many (federal at least) IMT members, the ability and time to consider incident issues is severely limited. If we are to truly cultivate and expand expertise, we must invest in the time to reflect, to share, to learn--and it must be more than the drive home after an incident or a couple of days at a team meeting in the spring. The current and future challenges are too great for us to allow anyone's expertise to stagnate or diminish. Apologies for not writing much recently. Lots of wildland fire work here in SW OR, summer days with the family, a new puppy, and getting the daughters ready for another school year. I'll do better.

_____ Jim As a communicator, it's easy to get wrapped around the axle trying to remember what we can and cannot talk about. For instance, in the wildfire world, I saw a lot of skittishness last year when it came to air tankers--and for good reason. Contracts and such are complicated things beyond most PIO's (and ICs, FMOs, and agency administrators) understanding. When it comes to flying things that weigh a bunch and get politicized easily, it becomes even tougher to not only get it factually correct, but to also navigate through all the potential political potholes.

Yet just because a topic includes complex and controversial issues does not mean we should surrender the whole conversation to others. Donations for perceived responder needs are an issue on most incidents. The tales of donation problems are legion and range from mountains of socks and foot powder to truckloads of dog food and sunglasses. The demands on the logistics section and the incident management team are enormous on any incident and adding the burden of managing the intake and fair distribution of donations is beyond most. If the incident is not willing and able to accept the donations, a reflexive public outcry is always a possibility. Like many things in our complicated society, there is no good way to deal with the commendable actions of donations.

|

Occasional thoughts on incident response, crisis communications, wildland fire, and other topics.

Docendo disco, scribendo cogito. Blog DOB: 4/26/2018Copyright © Jim Whittington, 2019. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed