|

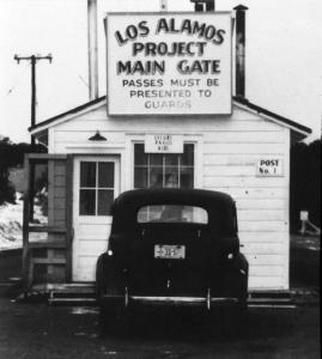

In chapter 5 of Theorizing Crisis Communication, authors Timothy Sellnow and Matthew Seeger refer to the Incident Command System (ICS) as "rigid, hierarchical" and suggest ICS "does not account for emergent groups or flexibility as disaster situation changes." They further quote another scholar who describes ICS as "ineffective for large-scale disaster response because its centralized structure cannot mesh with the political and social realities inherent in American Society." Finally, the last and most significant criticism of ICS documented in the chapter is that "the bureaucratic model lacks flexibility and does not accommodate collective improvisation..." Needless to say, these criticisms do not match my experiences.  To be fair, Sellnow and Seeger's book is a reference point for current academic thought on crisis communications and they are not necessarily advocating this view of ICS. They do note in one sentence that a 2001 paper by Bigley and Roberts "argued that ICS is actually a more flexible system allowing incident commanders the ability to adapt to the situation." In other Communications tomes, ICS is treated much the same if mentioned at all. For instance, in two widely used sources, ICS does not even appear in the index of Ongoing Crisis Communication by W. Timothy Coombs or The Handbook of Crisis Communication edited by Coombs and Holladay. Much of the Communications literature revolves around best practices developed from corporate reputation management cases. Because of a bureaucratic heritage and governmental support, ICS is often treated as a "rigid" paramilitary or hierarchical system by crisis communication scholars and other academics, including in a surprising number of emergency management publications. This categorization seems to be based on studies looking at local organizations using ICS, an examination of the originating documents for ICS, or perhaps it is influenced by the ICS position chart, which admittedly resembles a typical hierarchical organization. The simplistic views are like Newtonian physics in that ICS is observable where academics can easily go for research, but the conclusions break down upon further thought and when things get larger and more complex.  As it has evolved, ICS is not a rudimentary scheme. When fully deployed and completely enabled in support of an organization with time prior to work out the challenges, ICS is not only flexible and adaptive, it is also a radical construct that challenges the assumptions of parent organizations. At the highest level of command and coordination, ICS may be the closest thing we have in the United States to a meritocracy. Now, it's not perfect as we are humans after all, but in general, it does not matter who you know, who your parents are, or how much money you have. If one does not have the training, the experience, and in many cases, the temperament, one does not get the job. Similarly, the people most suited to managing a dynamic, stressful, and complex incident under ICS are, in my experience, usually not the same people who are most successful running the parent organization. The skills needed to acquire the corner office are not the same set needed to manage a crisis. In many cases, those skill sets are in conflict. The mechanisms of scalability are key to ICS as is the incentive and necessity to incorporate those affected by the incident into the decision-making process. As an example, most incident management teams carry one Liaison Officer. However, on the 2017 Eagle Creek Fire in the Columbia Gorge, there were five Liaison Officers at one point because of the complexity of the economic impacts and the number of stakeholders that included utility companies, railroads, several counties with several sheriffs, the Portland Water Bureau, the Coast Guard, many state agencies, and a host of private and citizen groups. (I think the Pearson's SW IMT did a great job of managing expectations and reducing stress and conflict for all parties involved.) For large-scale disasters, ICS has proven itself more than a few times. Of course, a massive-scale disaster like a Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake will tax any system, but I am certain that within a short period, the principles of ICS will help organize the response. Examining small, short duration, operations-heavy incidents like search and rescue colors the academic research because the Operations Section is the one part of ICS that must be hierarchical to account for all on-the-ground responders and their safety. The remaining organization is much more horizontal and during incidents that extend over days or weeks, the emphasis might be on complexities affecting other parts of the IMT. I don't see how academic conclusions can be drawn about ICS without looking at incidents that overwhelm local resources for an extended period. They completely miss the resource scaling, logistics concerns, planning conundrums, and the social and political pressures that all build as the team and community try to deal with an ongoing and perhaps elevating crisis. Also, based on my anecdotal observation of the wildland fire agencies, it takes a generation or more to fully adapt to ICS and one of the benchmarks is that the parent organization accepts that crises are different and trusts specialists to manage those crises outside of the regular organizational structure. I'm not sure wildland fire or the Coast Guard--an early adopter of ICS--completely meet the ideal, but both groups are much further along than those who started using ICS after 9/11 with the advent of the Department of Homeland Security's National Incident Management System. The reason is that when ICS is first brought in, the tendency is to paper it over the existing organization: the supervisor becomes the IC, the Public Affairs Officer becomes the PIO, the maintenance crew becomes Logistics, and so on. It takes tireless advocates and usually a series of failures before a toehold for legitimate ICS within the organization can be established. The tension is compounded because in times of crisis people gravitate to the comfortable, which in a nascent ICS structure is almost always their regular jobs. When this happens, the crisis response is bound to have problems. Again, anecdotally, I think leadership has to turn over at least once before the potential of ICS can be fulfilled. (It would be great to have some academic studies looking at this.) There is also the problem of the parent organization who may acknowledge the necessity of ICS but who come to resent the reliance on ICS and those who make it work. I can't tell you how many times during my career I came back to the office after a stressful assignment to be greeted by snippy comments from supervisors like, "Did you enjoy your vacation?" (I think I'll put this on the list of future topics because there is a lot to say on the organizational psychology at play that needs much more attention than we give it -- and if wildland fire and other organizations are truly striving towards the ideal, more attention definitely needs to be paid.)  Several (Ok, make that many) years ago, I had the opportunity to observe and comment on a simulation at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL). The training incident was based on a cloud of radioactive tritium gas escaping (tritium is used to enhance the yield of nuclear weapons), and was scheduled for four hours. Throughout the simulation, there were various media inputs and demands for information. As you might expect, this would be an instant national story if it really happened. With about 10 minutes left in the simulation, a press release was finally issued. That was the only public communication for the exercise. During the review, the LANL public affairs personnel were ecstatic that they were able to get a press release out in under four hours, considering it usually took them much longer. Under questioning, they followed essentially the same approval process--through a myriad of officials--as they did for a regular press release. So much effort was put into getting the press release done by the end of the four hours, that there was little comprehension the release was outdated and events had passed them by. I'm not sure what the current protocol is at LANL, but it is a great story that illuminates the difference between the everyday and the crisis which certainly still applies to many organizations. I think there is a wealth of potential academic studies looking at organizational barriers to crisis response and there are more than a few dissertations for crisis communication doctoral students on how the parent organization and the crisis responders interact and influence crisis communications. Organizational psychology under stress. Of course, I also think a good suite of studies on ICS as practiced on large incidents by the wildland fire community and the Coast Guard will help provide a more complete understanding to practitioners, academics, and especially those organizations grappling with the generational challenges of implementing ICS. As I said in the Terms post, we are definitely at the point where we need more and better academic support to understand and manage the increasing complexities of emergency management and crisis/disaster communications. It's getting more difficult and we need academic-supported doctrine and intellectual frameworks to help us. Disclaimer: I'm not only a practitioner of the Incident Command System, I am a proselytizer. ____ Jim Copyright © Jim Whittington, 2018, All rights reserved. Academic use approved with notification and attribution.

3 Comments

Pete Buist

5/15/2018 06:55:55

As an ex-Ops and now PIO1 and LOFR (with 51 sesons of fire experience,) I agree with Jim's analysis. When applied correctly, ICS is in fact the antithesis of most of the things the nay-sayers are claiming. I think the reason that many corporate (and military) entities have issues with ICS is because ICS is based on "experience and training/qualifications" as opposed to RANK or POLITICAL POWER. These entities are very uncomfortable with a lower ranking individual being temporarily elevated into a position of authority just because they know more and have more experience about the subject at hand. ICS effectiveness is on full display countless times each season. Others could take a lesson.

Reply

6/9/2018 15:16:49

Some of us simply don't have the skills to report what has been happening. These type don't know how to give close attention to details and mostly they report false information. It's not good for everyone. Someone has to be assigned this job because clearly, not everyone can handle this. It would be better if it's a third party who will not be directly involved with whoever is making the decisions.

Reply

JIM

5/15/2018 08:55:31

Nicely said Pete. A more elegant phrasing than my attempt at describing the tension ICS creates within organizations.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Occasional thoughts on incident response, crisis communications, wildland fire, and other topics.

Docendo disco, scribendo cogito. Blog DOB: 4/26/2018Copyright © Jim Whittington, 2019. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed